When the Internet Goes Dark: Building an SMS-to-AI Gateway for the Offline World

Mis à jour :

In April 2025, Barcelona experienced a massive internet outage that left millions without connectivity. A few months later, Red by SFR users in France faced similar issues. These events got me thinking about our dependency on constant internet access. What if you could still access AI assistance with nothing but a basic phone and SMS? This is the story of how I built exactly that.

The Problem: Always Connected, Until You’re Not

We live in an era where asking a question means reaching for a smartphone, opening an app, and assuming the internet will be there. But what happens when it isn’t? Infrastructure failures or simply being in a remote area can cut us off from the information we’ve grown accustomed to having at our fingertips.

There’s also a more personal motivation: I’d like my future kids to not need a smartphone too early. Call me old-fashioned, but I believe they should still have access to information, useful tools, and a way to contact people—without the endless scroll of social media. A simple phone with SMS capabilities could be enough.

The Barcelona and Red by SFR incidents reminded me that SMS has been around since 1992. It works on 2G networks. It works when data networks are congested. It works almost everywhere. Could I bridge this resilient, decades-old technology with modern AI?

The Hardware: A Tiny Board with Big Ambitions

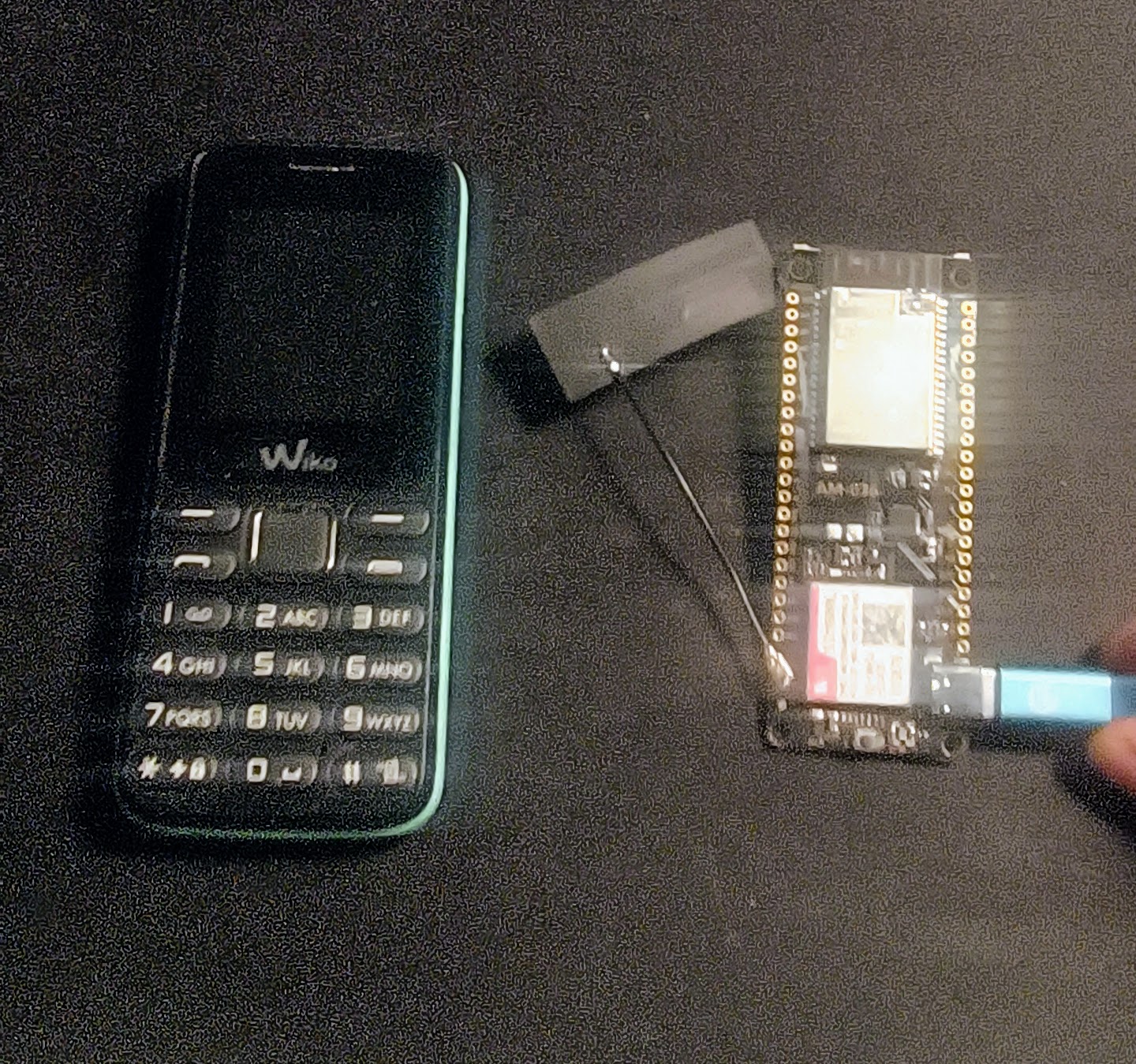

I purchased a LilyGo T-Call SIM800 specifically for this project. It’s a neat piece of hardware: an ESP32 microcontroller paired with a SIM800 GSM modem, all on a single compact board. For around 15 euros, you get WiFi, Bluetooth, and cellular capabilities. The ESP32 handles the logic while the SIM800 manages SMS communication.

The concept was simple:

- Receive an SMS on the device

- Forward the message to OpenAI’s API via WiFi

- Send the AI’s response back as SMS

Simple in theory. The implementation, as always, had other plans.

First Challenge: Getting the Modem to Talk

The SIM800 communicates via AT commands—a protocol dating back to the Hayes modem era of the 1980s. There’s something almost poetic about using commands designed for dial-up modems to interface with cutting-edge AI.

Getting the modem to reliably receive SMS messages was my first hurdle. The SIM800 can notify you of incoming messages in two ways: direct notification (+CMT) which pushes the message content immediately, or storage notification (+CMTI) which tells you a message was stored and you need to fetch it. Different carriers and network conditions can trigger either mode, so the code needs to handle both to be reliable.

modem.sendAT("+CMGF=1"); // Text mode

modem.sendAT("+CNMI=2,2,0,0,0"); // Direct SMS notification

modem.sendAT("+CSCS=\"UCS2\""); // Unicode support

The AT command syntax is straightforward once you find the right documentation—scattered across forums, datasheets, and old blog posts.

Second Challenge: The Accent Problem

I’m French. I write in French. French has accents: é, è, à, ç, ê… SMS wasn’t designed with Unicode in mind. The GSM 7-bit encoding handles basic ASCII beautifully but mangles anything beyond that.

I spent hours trying to make UCS2 encoding work properly. The theory is elegant: every character becomes a 4-digit hexadecimal code. “Bonjour” becomes “0042006F006E006A006F00750072”. I could convert incoming messages with accents correctly, but sending them back? The modem never cooperated fully.

After much frustration—the kind where “café” arrives as “caf?” and you question everything you know about character encoding—I made a pragmatic decision: convert everything to uppercase. CAFE instead of café. It’s not pretty, but it works reliably. Sometimes the practical solution beats the elegant one.

Third Challenge: Conversations Have Memory

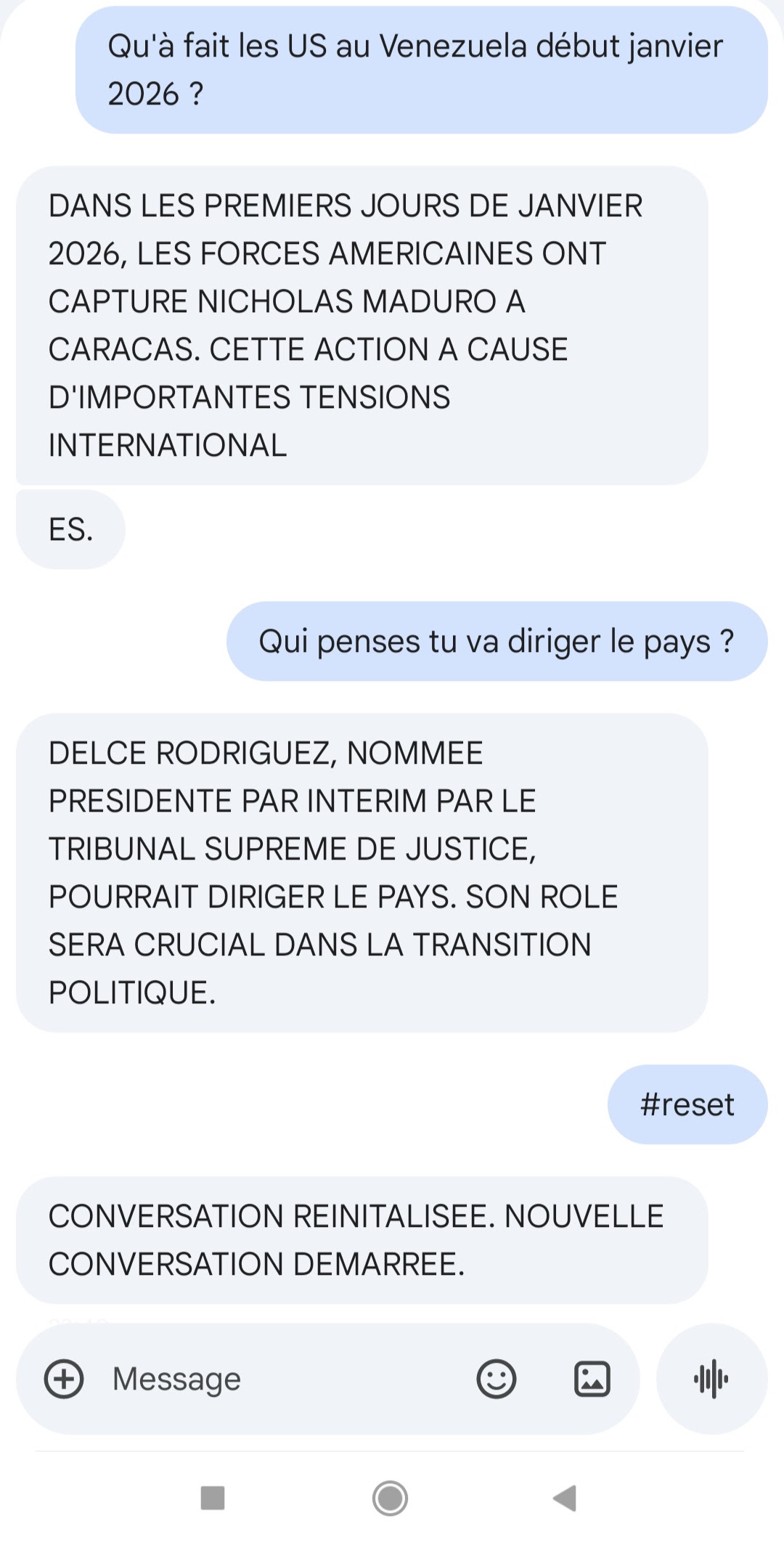

An AI that forgets every message isn’t very useful. “What’s the capital of France?” followed by “What’s its population?” should work without re-stating “Paris.”

I implemented per-phone-number conversation tracking using OpenAI’s conversation format. Each caller gets their own message history that’s sent with every API request, allowing natural multi-turn dialogues. The device remembers context for up to 5 simultaneous conversations—enough for a family or small group.

std::map<String, std::vector<Message>> conversations;

Each message exchange appends the user’s question and the assistant’s response to the history. When the conversation gets too long or you want to start fresh, just send “RESET” and it clears your history.

This small feature transformed the project from a novelty into something genuinely useful.

Fourth Challenge: Long Responses, Short Messages

AI tends to be verbose. SMS is limited to 160 characters in GSM encoding (or 70 in UCS2 mode with Unicode). A typical ChatGPT response might be 500+ characters.

The solution: automatic message splitting. When a response exceeds the limit, the code calculates how many parts are needed and splits the text accordingly. Each part gets a prefix like “[1/4]”, “[2/4]” so you know where you are in the sequence. The algorithm reserves space for this prefix when calculating split points, ensuring no content gets cut off.

Timing matters too. Send messages too quickly and the modem gets overwhelmed. I settled on 3-second delays between parts—a compromise between reliability and responsiveness. The user’s phone receives them in order and can read through the full response.

The Result: AI in Your Pocket, No Internet Required

The final system works like this:

- Send an SMS to the device’s phone number

- The LED blinks twice—message received

- Ten rapid blinks—querying the AI

- Five blinks—sending the response

- Your phone buzzes with the answer

For the user, it feels like magic. Text a question from a basic Nokia, receive a thoughtful AI response seconds later. No app, no data plan, no WiFi on their end. Just SMS.

Technical Stack

For those who want to build their own:

- Hardware: LilyGo T-Call SIM800 (~15€)

- Framework: Arduino on ESP32 via PlatformIO

- Libraries: TinyGSM, ArduinoJson, ArduinoHttpClient

- AI Backend: OpenAI API (via web requests)

- Encoding: Uppercase ASCII (after giving up on UCS2)

- Power: USB or battery via onboard PMU

The code handles edge cases I never anticipated: malformed messages, API timeouts, modem resets, WiFi reconnection. Embedded systems teach humility.

Lessons Learned

Resilience is undervalued. We build systems assuming perfect connectivity. The interesting engineering happens when that assumption breaks.

Old technology has wisdom. SMS has survived because it’s simple and robust. There’s value in protocols that “just work.”

Sometimes good enough is good enough. I could have spent more weeks fighting UCS2 encoding. Instead, uppercase text works and I shipped something functional.

What’s Next?

The current prototype lives on my desk, tethered to USB power. Future iterations might include:

- Local LLM: Running a small language model and gateway to manage the history without relying on openai

- Agent tools: Adding capabilities like sending emergency, managing a todo list, or setting reminders. Tools beyond internet search.

- Social experiment: Leaving the phone number in random public places and letting strangers chat with a quirky local LLM.

- Voice calls: The SIM800 supports voice—imagine calling a number and talking to an AI

- Remote deployment: Setting up the device at my parents’ house so I can use it even if Paris goes dark

But for now, it works. When the next outage hits, I’ll have a backup. A tiny board that bridges 1992 and 2024, proving that sometimes the best solutions combine the old and the new.

The LilyGo T-Call SIM800 is available from various electronics retailers. The complete source code for this project will be available in my github.